杨

In Mandarin, it is pronounced as “yang” while in the Hakka (or Kheh) dialect, it is pronounced “yong”. It is the sixth most common surname in China. “Yang” means poplar (a kind of tree).

In this chapter, we will focus on three aspects relating to the Yang / Yong clan. The first looks at the occurrences of the surname within the various dynasties of China. Given that Yongs are predominantly from the Hakka dialect group, the second focus is on the geographical areas in China where the Hakkas either originated or where they can be found in larger numbers. The third is on the various migratory waves of Hakkas as they ventured towards Nanyang and other regions.

But first, a little bit more about Hakkas in general. Hakkas or Khehs are a unique ethnic group of “Han” Chinese. They are also a dialect group that literally means “guest people”. Hakkas are also unique because while other groups can claim a coherent homeland of their own, Hakkas live with few exceptions in dispersion, as minorities scattered around southern China. Indeed, the Hakkas are said to have taken to the road in five separate major migrations (see later). The nickname "Jews of Asia" intimates these mass migrations and the pioneering spirit of the Hakkas.

Hakkas practiced more equality of the sexes than other Chinese dialects. The Hakka women were strong and energetic. Traditionally the Hakkas never bound the feet of their daughters. This was because the Hakka women had to work in the fields while their men were away fighting or protecting their villages from attack by hostile non-Hakka neighbours. The Hakkas simply could not afford to have women unable to work or to walk. While other Chinese did not want to marry a girl with unbound feet, the Hakkas did not want to marry a bound-feet girl ! Hakka girls were also rarely sold as slaves or concubines, but sometimes they were sold as “child brides”.

Yang / Yong in Dynastic China

Research documents on Chinese surnames reveal that there are many versions of the origin of the Yang or Yong surname. Some say that it came from an official position while others thought it was named after a place.

One study suggests that Yangs are the descendents of the Xi Zhou Dynasty. The third son of Zhou Wu Wang, Tang Shu Yu was awarded the land of Jin. His descent Jin Wu Gong was awarded the Yang city (Hong Dong of Shanxi Province) and bore the last name of Yang and Yang She (Goat Tongue). Around 514 B.C., a rebellion took place, and both the Yangs and the Yang Shes were persecuted. They migrated south to Hong Nong Hua Yin. About 90% of famous Yangs in the history came from Hong Nong Hua Yin. The hometown is south of Ling Pao in Henan Province.

But most believe that the Yang clan was an offspring of the Jin family, which was said to have descended from the legendary emperor Huang Di. It was said that King Wu’s grandson, Bo Qiao of the Zhou dynasty, was made marquis of the Yang county. He later adopted the county’s name as his surname.

Sui Dynasty (AD 581-618)

The Sui Dynasty replaced the chaotic period of the Northern and Southern dynasties and unified China. During Sui administration, the two emperors came from the Yang clan. Yang Jian or Emperor Wen, the first Sui emperor, was a hardworking emperor who brought sociopolitical stability and economic prosperity to China. Unfortunately he was killed by his second son, Yang Guang who became Emperor Yang. Under his rule, the Grand Canal was dug linking North China with the Southern regions. High taxes and the emperor’s tyranny triggered off a series of rebellions. Emperor Yang was murdered by subordinates and the Sui Dynasty came to an end and was succeeded by the Tang Dynasty.

Tang Dynasty (AD 618- 907)

During the Tang Dynasty, the Yang clan was very prominent in Shanxi, which was its homeland. Towards late Tang, many people were forced to migrate to the south because of war. The Yang clansmen followed suit and settled in Zhangzhou, Fujian province.

Song Dynasty (AD 960-1276)

By the Song dynasty, Fujian virtually became the heart of the Yang’s.

Yang Ye, a reknown general of the Northern Song dynasty, was captured by the invading Liao army during a battle. He was then 60 years old, but rather than submit to the invaders, he went on a hunger strike and died. Several of his sons also died while defending their country’s northern border. Yang Ye’s northern exploits were widely proclaimed and he became a legend. His wife and daughters-in-law were also famed for their military prowess.

Besides Yang Ye, there were other famous figures produced by the clan. One was Yang Zhu, a philosopher who lived during the Warring States period. Yang Zhu was against the concept of equal love for all as advocated by Mo Zi. He was also against Confucian teachings. He advocated that one should value one’s own life, resist those who do us harm but not to do harm to the innocent.

Yang Wan Li (A.D. 1122-1206) was an outstanding poet during the Southern Song period. Concerned with the welfare of his country and people, he often spoke out against social ills. His poems were characterized by simplicity in style and by his closeness to the people’s life.

Hakka inhabited areas in greater China

Today Hakkas can be found in parts of Guangdong, Jiangxi and Fujian, and in pockets in Sichuan, Hunan, Guangxi, Yunnan, Hainan and Taiwan. From the 16th century, they came to identify Meixian and its surroundings (formerly the Jiaying Prefecture) – at the conjunction of the Lingnan, Gan Yangzi, and Southeast coast marcoregions – as their homeland. For two centuries before that time, this upland area was isolated from the valleys, and during this time, the Hakkas adapted to the marginal, hilly environment.

The exceptional sense of solidarity, a response to the hostility of neighbouring Chinese groups, may be seen in the unusual and defensive style of their dwellings: circular, multi-story structures with hundreds of rooms arranged round a communcal space and surrounded by a mud wall.

Fig 2-1: Hakka villages in China, with typical round structures

The brutal competition between the Hakkas and the local inhabitants (“pun ti” meaning local) for scarce land turned their villages into ethnically separated armed camps. Eventually there was much hatred and animosity built up between the Hakkas and locals, until all quarrels came down to brutal clashes. The climax of the successive outbreaks of violence was the large-scale wars of the West River region in the 1850s.

Against the backdrop of the Hakka-local fighting, itself linked to a downturn in the Lingnan regional economy, that the Society of God Worshippers evolved. Started by Hakka converts to a new kind of Christianity, the society met the needs of embattled, dispossessed Hakkas. It became militarized and grew into the revolutionary army that swept through China in the 1850s in the guise of the famous Taiping Rebellion, heralding “the greatly magnified power of ethnicity combined with religion, a power that almost ended the life of the dynasty” .

Migrations of the Hakka people

Many writings about the Hakkas describe them as having originated in the Central Plains, the Huang (Yellow) River Basin in northern China.

There are two alternative theories that explain the origins of the Hakka.

The first theory is that the Hakkas are the descendents of the half million soldiers sent by Qin Shi Huang Di, the first Emperor of China, to the south in 214BC. After the collapse of Qin around 207BC, many of these soldiers stayed on and inter-married with the local Yue women.

Migration 1

The first migration was during the Period of The Sixteen Kingdoms of the Five Barbarians 317AD to 581AD. Due to the invasion of the Non-Han Chinese from the Siberian steppes the Hakka People crossed the Son Of The Ocean (Yangtze Jiang) and settled down in the provinces of Anhui and Jiangxi.

Migration 2

The second Hakka migration occurred at the end of the Tang Dynasty (618AD to 907AD) and the beginning of the Song Dynasties. This period was called The Five Dynasties and the Ten Kingdoms, and lasted from 907AD to 954AD. The predecessors of the Hakkas were displaced to southern Anhui, southwestern Jiangxi, southern and western Fujian, and the border area of Guangdong.

Migration 3

The third Hakka migration started around 1274AD during the Song Dynasty (960AD to 1279AD).After various fierce battles, the Hakka people fled when conquering Mongolian armies took control of the Central Plains and the royal Song household fled south. Since the provinces of the middle and south China were already settled by the earlier migrants, the Hakkas had to settle farther south. They arrived in the provinces of Guangdong, Fujian, Taiwan and North Vietnam.

Migration 4

The fourth Hakka migration occured around the end of the Ming Dynasty up until the time of the Qianjia Reign at the beginning of the Qing Dynasty (1644AD to 1911AD), and was a result of factors including the swelling population and the Manchurian armies sweeping southward.

They migrated from southern and northern Guangdong and southwestern Jiangxi to the central and coastal regions of Guangdong, as well as Sichuan, Guangxi, Hunan, and Taiwan. Smaller numbers headed to southern Guizhou.

Zhang Xian Zhong, the "Yellow Tiger", the rebel during the end of Ming had invaded Sichuan province, stamping out all his opponents. He killed thousands and was said to have almost depopulated Sichuan. Later the Qing Government encouraged the Hakka People living in southern China to immigrate to Sichuan province and paid eight ounces of silver per man, four ounces per woman or child. Many Hakkas accepted the offer and settled down in Sichuan.

Migration 5

The fifth and the last migration took place at the end of the Taiping Revolution (1851AD to 1864AD). To the Hakka, this revolution is often considered their most glorious epic because the leader, Hong Xiu Quan, was a fellow Hakka. He established a Heavenly Kingdom in Nanjing. However it failed to oust the Qing Government and was destroyed by the Imperial Qing army with the help of the Western Powers.

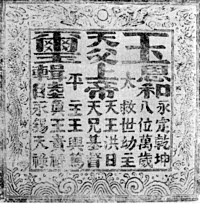

Fig 2-2: Hong Xiu Quan, a Hakka & leader of the Taiping Revolution

After the destruction of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom in 1864AD the Manchus killed many men, women and children with the surname Hong. Many fled or changed their surnames.

Due to these massacres many Hakka People migrated to Nanyang (or South East Asia). Some of them went as far as Brazil, Panama, U.S.A. and even Africa.